Deadly Planets

September 2006By By Patrick L. Barry and Dr. Tony Phillips

By Patrick L. Barry and Dr. Tony Phillips;Interested? Don't be. Going there would be the last thing you ever do.

>> Macro menumgr_macro_spaceplaceimage not found <<

The star is a pulsar, PSR 1257+12, the seething-hot core of a supernova that exploded millions of years ago. Its planets are bathed not in gentle, life-giving sunshine but instead a blistering torrent of X-rays and high-energy particles."It would be like trying to live next to Chernobyl," says Charles Beichman, a scientist at JPL and director of the Michelson Science Center at Caltech.

Our own sun emits small amounts of pulsar-like X-rays and high energy particles, but the amount of such radiation coming from a pulsar is "orders of magnitude more," he says. Even for a planet orbiting as far out as the Earth, this radiation could blow away the planet's atmosphere, and even vaporize sand right off the planet's surface.

Astronomer Alex Wolszczan discovered planets around PSR 1257+12 in the 1990s using Puerto Rico’s giant Arecibo radio telescope. At first, no one believed worlds could form around pulsars—it was too bizarre. Supernovas were supposed to destroy planets, not create them. Where did these worlds come from?

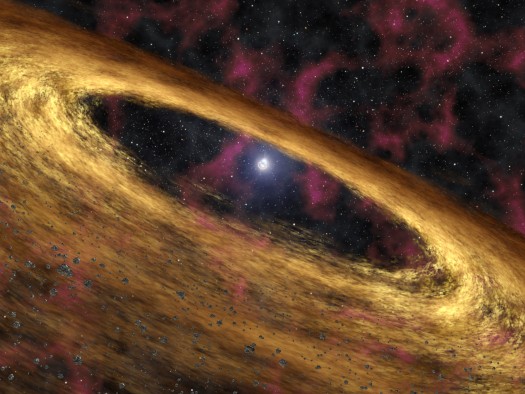

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope may have found the solution. Last year, a group of astronomers led by Deepto Chakrabarty of MIT pointed the infrared telescope toward pulsar 4U 0142+61. Data revealed a disk of gas and dust surrounding the central star, probably wreckage from the supernova. It was just the sort of disk that could coalesce to form planets!

As deadly as pulsar planets are, they might also be hauntingly beautiful. The vaporized matter rising from the planets' surfaces could be ionized by the incoming radiation, creating colorful auroras across the sky. And though the pulsar would only appear as a tiny dot in the sky (the pulsar itself is only 20-40 km across), it would be enshrouded in a hazy glow of light emitted by radiation particles as they curve in the pulsar's strong magnetic field.

Wasted beauty? Maybe. Beichman points out the positive: "It's an awful place to try and form planets, but if you can do it there, you can do it anywhere."

More news and images from Spitzer can be found at http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/. In addition, The Space Place Web site features a cartoon talk show episode starring Michelle Thaller, a scientist on Spitzer. Go to http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/en/kids/live/ for a great place to introduce kids to infrared and the joys of astronomy.

Artist’s concept of a pulsar and surrounding disk of rubble called a “fallback” disk, out of which new planets could form.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.