Superstar Hide and Seek

January 2009By by Dr. Tony Phillips

by Dr. Tony Phillips;But it is not impossible. In fact, there could be dozens to hundreds of such stars hiding in the Milky Way right now. Furiously burning their inner stores of hydrogen, these hidden superstars are like ticking bombs poised to ‘go supernova’ at any moment, possibly unleashing powerful gamma-ray bursts. No wonder astronomers are hunting for them.

Earlier this year, they found one.

“It’s called the Peony nebula star,” says Lidia Oskinova of Potsdam University in Germany. “It shines like 3.2 million suns and weighs in at about 90 solar masses.”

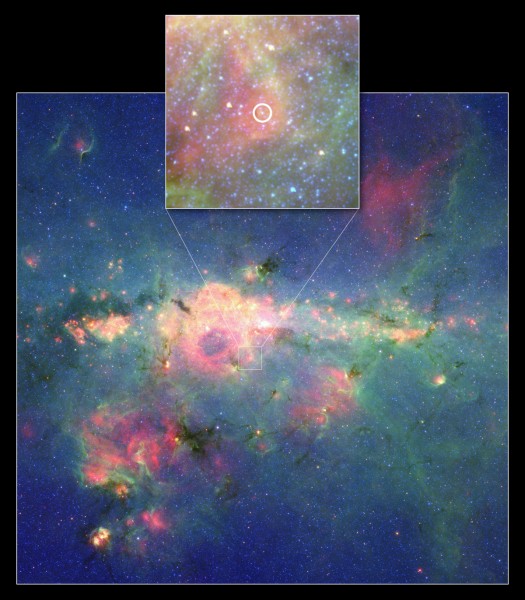

The star lies behind a dense veil of dust near the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Starlight traveling through the dust is attenuated so much that the Peony star, at first glance, looks rather dim and ordinary. Oskinova’s team set the record straight using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Clouds of dust can hide a star from visible-light telescopes, but Spitzer is an infrared telescope able to penetrate the dusty gloom.

“Using data from Spitzer, along with infrared observations from the ESO’s New Technology Telescope in Chile, we calculated the Peony star’s true luminosity,” she explains. “In the Milky Way galaxy, it is second only to another known superstar, Eta Carina, which shines like 4.7 million suns.”

Oskinova believes this is just the tip of the iceberg. Theoretical models of star formation suggest that one Peony-type star is born in our galaxy every 10,000 years. Given that the lifetime of such a star is about one million years, there should be 100 of them in the Milky Way at any given moment.

Could that be a hundred deadly gamma-ray bursts waiting to happen? Oskinova is not worried.

“There’s no threat to Earth,” she believes. “Gamma-ray bursts produce tightly focused jets of radiation and we would be extremely unlucky to be in the way of one. Furthermore, there don’t appear to be any supermassive stars within a thousand light years of our planet.”

Nevertheless, the hunt continues. Mapping and studying supermassive stars will help researchers understand the inner workings of extreme star formation and, moreover, identify stars on the brink of supernova. One day, astronomers monitoring a Peony-type star could witness with their own eyes one of the biggest explosions since the Big Bang itself.

Now that might be hard to hide.

Find out the latest news on discoveries using the Spitzer at www.spitzer.caltech.edu. Kids (of all ages) can read about “Lucy’s Planet Hunt” using the Spitzer Space Telescope at spaceplace.nasa.gov/en/kids/spitzer/lucy.

The “Peony Nebula” star is the second-brightest found in the Milky Way Galaxy, after Eta Carina. The Peony star blazes with the light of 3.2 million suns.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.