Total Lunar Eclipse for January

January 2019 :

Note: This article may contain outdated information

This article was published in the January 2019 issue of The Skyscraper and likely contains some information that was pertinent only for that month. It is being provided here for historical reference only.

Happy New Year everyone. I can’t believe another year has come and gone. While 2018 is a blur in this stargazers’ mind, I do unfortunately recall how weather conditions thwarted many of our observing sessions. After experiencing similar past depressing astronomical years I have often remarked that the new year couldn’t be any worse. Then Mother Nature proves me wrong. I am hoping 2019 begins a refreshing trend towards clear and transparent skies where the beauty of the Universe can be appreciated.

In this first column of the year I usually preview the best upcoming astronomical highlights. However, because January offers two main events, I will focus on those and defer my Astronomical Highlights for 2019 until my February column.

A great new year gift is the annual Quadrantid meteor shower which peaks on the night of January 3-4. This prolific display of shooting stars can produce up to 100 meteors per hour. However, under clear and moonless skies about 60 meteors per hour is a more reasonable expectation. Why this discrepancy? The meteor stream is very narrow. Only one to two hours is required for the Earth to sweep though the densest portion of it. So location, location, location, is the key to observing the higher rates. If time permits don’t give up unless you have to. I did so one year and missed a great outburst of shooting stars. As agent Maxwell Smart would say, “Missed it by that much.”

Furthermore, despite the potential for lots of meteors, many casual stargazers who live in colder regions do not place this shower high on their observing list. The August Perseids are more popular. However, I’d rather dress up for the cold than swat mosquitoes!

While these Quadrantids can appear anywhere in the sky, their radiant point (the area of sky from where the meteors appear to originate) is not far from the end star, Alkaid, of the Big Dipper’s handle. From midnight till dawn, this area of sky will rise higher and higher above the northeast horizon, and by 4:00 a.m. this region of the sky will be almost at zenith (directly overhead). You’ll know you’ve spotted a Quadrantid meteor if its dust train through the sky points back to the radiant point. A waning crescent Moon will rise at around 5:52 a.m. locally so it will not interfere with observing as many shooting stars as possible.

I still recommend that you get comfortable in a lounge chair to conduct your observing session. Just be careful that you do not get frostbite.

The Quadrantid meteors blaze across the sky at 25.5 miles per second. The majority of them are blue in color.

The grand event for January occurs on the night of January 20-21 with a total lunar eclipse. If clear skies prevail we will have the opportunity to observe this eclipse in its entirety. Totality doesn’t begin until just before midnight on Sunday night, so I expect there will be some bleary-eyed folks at work on Monday morning.

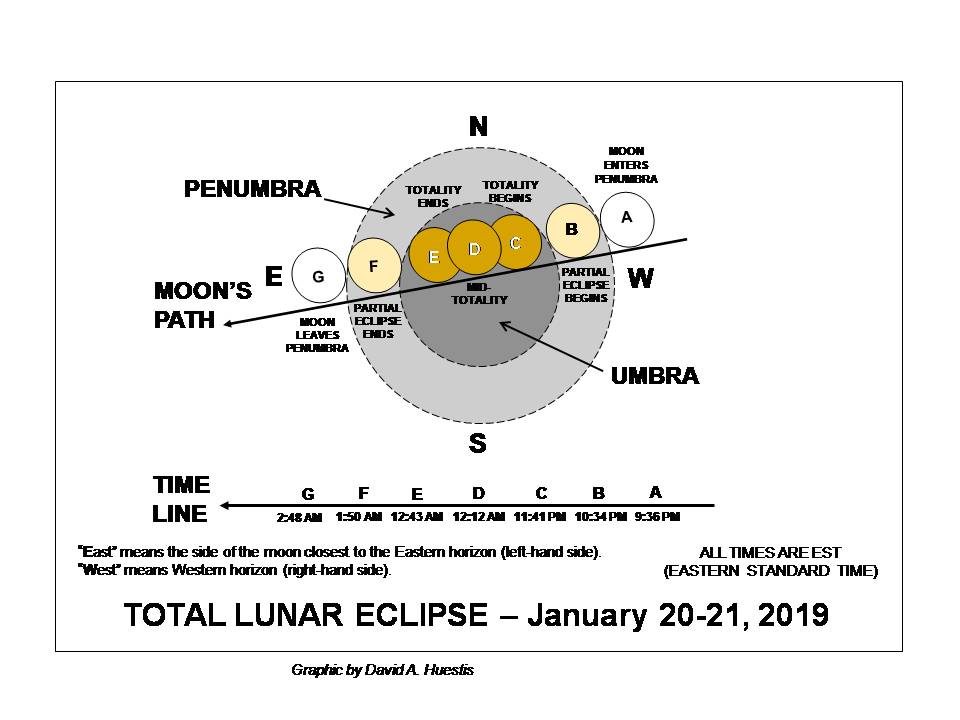

Please cut out the accompanying graphic for the times of specific “phases” of this eclipse. You can easily reference this information while you are outside enjoying the view. Beforehand you should review the following narrative to refresh your knowledge of what to expect.

For a total lunar eclipse to occur the Sun, Earth and Moon must be in alignment. With the Earth positioned in the middle of this celestial ballet, its shadow is projected onto the lunar surface. The duration of such an eclipse, particularly of totality, is determined by how precisely the three bodies are aligned. January’s eclipse lasts a total of five hours and 12 minutes, with totality lasting one hour and two minutes.

The eclipse technically begins at 9:36 p.m. when the Moon slides eastward into the Earth’s lighter undetectable penumbral shadow. Only as the Moon slides deeper into the shadow will a keen-eyed observer discern a subtle darkening of the lunar surface. It is just prior to the Moon entering the Earth’s dark umbral shadow that one will notice that the moonlight looks somewhat subdued.

When the Moon first encounters the umbral shadow at 10:34 p.m., the partial phase of the eclipse begins. For one hour and four minutes the Moon will move deeper and deeper into the shadow, generally from left to right. Then at 11:41 p.m. totality begins when the Moon will be completely immersed in the Earth’s umbral shadow.

I do not expect the Moon to disappear from view completely (as it has during past eclipses) for two reasons. First, it will not be sweeping through the central portion of the dark umbral shadow (see graphic). Second, no recent volcanic eruptions have spewed any dust into the Earth’s upper atmosphere to significantly redden the Moon’s appearance.

Enhance your view of this eclipse with binoculars or a small telescope. The colors often change as totality progresses, so watch carefully. For one hour and two minutes totality is truly a beautiful sight to observe.

Totality ends at 12:43 a.m. when the Moon begins to leave the dark shadow and sunlight returns to its surface. For one hour and seven minutes the partial phase will continue until the Moon’s face is completely illuminated once again at 1:50 a.m. For a while the Moon’s light will still look somewhat subdued as the Moon will remain within the lighter penumbral shadow until 2:48 a.m. when the eclipse ends. In a dark sky you may be able to detect this shadow soon after the partial phase completes. Thereafter the remaining penumbral phase will hardly be noticeable at all.

Please note the sky in the vicinity of the Full Moon before the eclipse begins. As the eclipse progresses and the sky darkens watch as the surrounding constellations become more visible. In particular, watch as the Beehive Cluster (M44), just about eight degrees to the upper right of the Moon emerges into visibility. Binoculars will help to reveal this beautiful open cluster of stats.

Weather prospects at this time of year are far from favorable, so let’s cross our fingers that Mother Nature will cooperate. The next total lunar eclipse visible from Southern New England after this one won’t be until May 15-16, 2022.

And finally, for you early risers who travel eastward during dawn’s early light to begin your work day will certainly notice a bright planetary duo above the eastern horizon during January. Those astronomical beacons are Venus and Jupiter. Venus is the brighter of the two worlds. Each day they will draw closer to each other. On the morning of January 22 only 2.5 degrees will separate this pair. Thereafter they will drift apart, but on the 31st a waning crescent Moon will be positioned between them for a nice photo op!

Keep your eyes to the skies for 2019 and always.