Skylights: July 2023

July 2023 :

Note: This article may contain outdated information

This article was published in the July 2023 issue of The Skyscraper and likely contains some information that was pertinent only for that month. It is being provided here for historical reference only.

Earth is at aphelion, the farthest point in its orbit around the Sun, on July 6. Just before midnight, Earth will be 1.01668 AU (152.093 million kilometers) from the Sun. This is 3.395% (0.03339 AU, 4,994 million kilometers–13 times the distance to the Moon) farther away than on January 4, when Earth was at perihelion.

After spending 29 days in Gemini, the Sun enters Cancer on July 21.

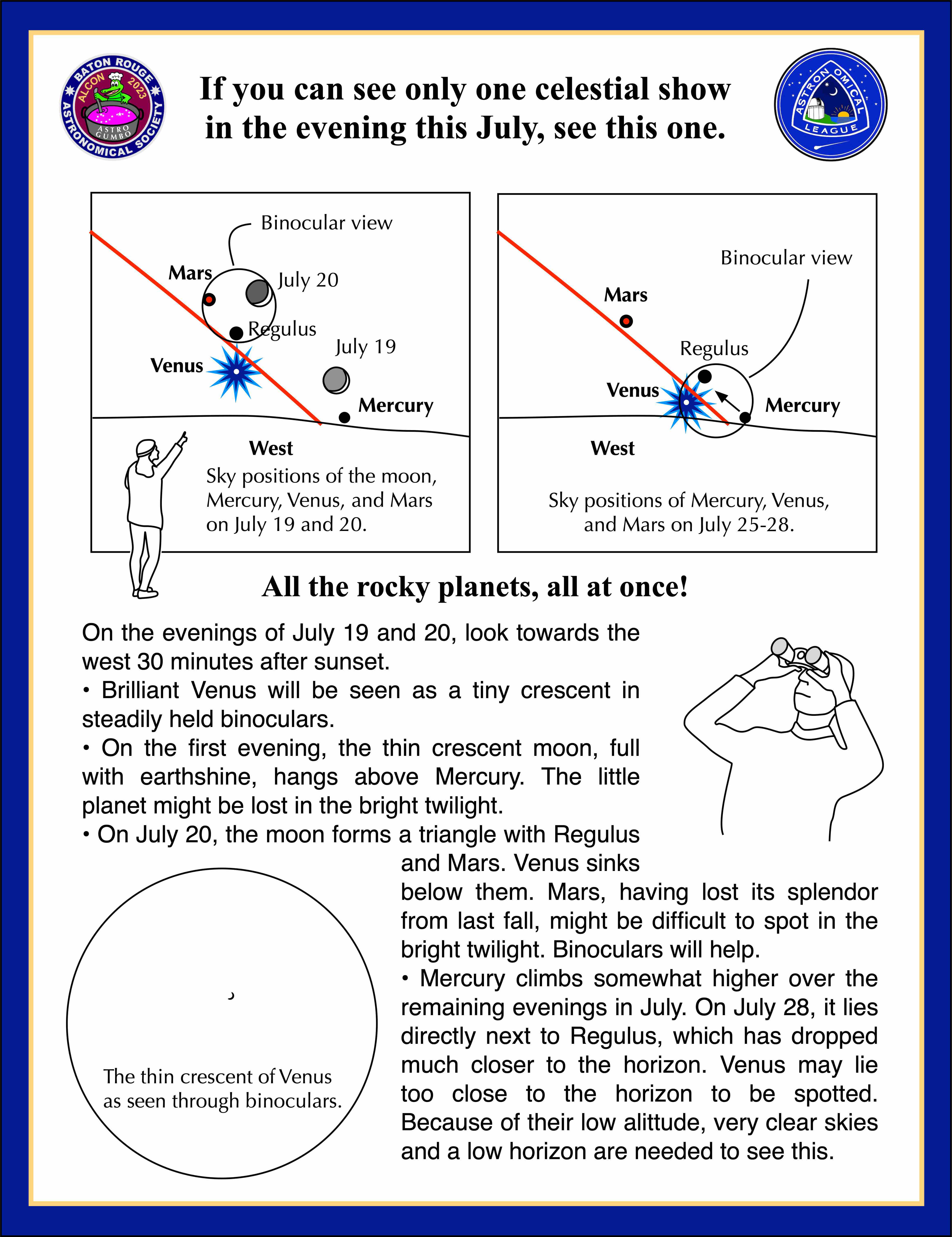

An evening apparition of Mercury occurs in July, after the innermost planet passes superior conjunction on the 1st. Although it remains low throughout its presence in the evening sky this month – it remains visible no longer than 67 minutes after sunset – there are several opportunities to observe it next to some other familiar objects.

Although a challenge to observe, Mercury is positioned within the northern portion of M44, the Beehive Cluster in Cancer, on the 14th.

On the 18th, the very young, 1.1-day crescent Moon lies just 5.2° to the right of Mercury, nearly parallel to the horizon. The two should be fairly easy to locate with binoculars, given favorable conditions.

Latest Mercuryset for this month’s evening apparition occurs at 9:20pm EDT on the 20th.

On the 21st, you can find Mercury 10° to the right of Venus, on a line nearly parallel with the western horizon.

Perhaps the best night to view Mercury will be on the 28th, when the magnitude 0 planet stands in for Leo’s heart, as it will lie just 7 arcseconds south of magnitude 1.36 Regulus.

You will have noticed that the position of Venus is changing dramatically with each passing night in July. getting lower in the western sky after sunset As it approaches inferior conjunction in mid-August, its apparent separation from the Sun decreases. It is also moving southward, crossing the ecliptic on July 4, and continuing to move closer to the horizon throughout July, By the end of the month, it sets just 22 minutes after the Sun, making observing its large crescent fairly difficult.

Observing Venus with a telescope during the weeks leading up to its inferior conjunction also reveals its rapidly changing size and phase. At the beginning of July, when Venus is 0.49 AU away, the planet shows a 31.4% illuminated crescent 34 arcseconds across. By July 7, it will appear larger than Jupiter (37.4 arcseconds) and show a 26% illuminated crescent. By month’s end, at just 0.31 AU distant, Venus shows a 5.6% illuminated crescent that is 54 arcseconds across.

Over the past several months, Venus has appeared to have been chasing Mars, and it finally catches up with the Red Planet on July 1, when the two are just 3.5° apart, before Venus begins dropping back towards the Sun. This is the closest Venus and Mars will appear together until February 2024.

July is the final month to see Mars under dark sky conditions, as it begins to set during astronomical twilight on the 12th.

At over 2.2 AU from Earth, Mars shows a tiny, 4 arcsecond disk, barely larger than Uranus. Given its size, and the considerable airmass its light passes through, not much can be expected from observing Mars telescopically, but at magnitude 1.6, it is worth tracking with binoculars before it becomes difficult to view in twilight.

Mars spends the month of July in Leo, and during the first half of the month, it can be seen doing a celestial dance with Venus and Regulus, being within 1° of Leo’s alpha star on the 10th and 11th.

The 2.9-day crescent Moon appears 2.8° to the right of Mars on the 20th, and if you are interested in a telescopic challenge, magnitude 9.2 asteroid 2 Pallas lies just 2.7° southwest (almost directly below) Mars that same evening, when Pallas is just 29% farther away from Earth, at 3.00 AU, compared to Mars’s 2.47 AU.

Now that Saturn is an evening planet, rising just after 11:00pm EDT in early July, it is high enough to observe telescopically in the early morning hours, and even before midnight at month’s end. You may notice that Saturn’s ring plane angle has narrowed considerably since last year, and now some of its inner moons can be seen transiting Saturn, as well as disappearing behind the planet or its shadow. While these events are not as easy to observe as the transits and eclipses of Jupiter’s Galilean moons, it is worth noting, and that it is possible to observe or image them with a large telescope.

On July 6, the 19-day waning gibbous Moon passes 3.1° to the south of Saturn.

July is the best month to observe Pluto, which reaches opposition on July 21. At a distance of 33.80 AU, the dwarf planet shines at a faint 14.4 magnitude on the border of Capricornus and Sagittarius. Although Pluto crossed into Capricornus in March, its apparent retrograde motion has it meandering westward back into Sagittarius on July 8, where it will reside for the remainder of 2023. The globular cluster M75 is located about 1° to its north.

Jupiter, in Aries, rises at 1:45am EDT at the beginning of July, and becomes an evening planet, rising just a few minutes before midnight on the last evening of the month. The giant planet's four Galilean moons are aligned in order of their orbital distance to the east of the planet on the 2nd.

Neptune, in Pisces, is stationary on the 1st, and begins its retrograde motion. Our most distant planet is about 29.7 AU away, and shines at magnitude 7.8. It rises at about midnight in early July, and by 10:00pm EDT at the end of the month. This distant ice giant can be found 1.2° east-northeast of 5th magnitude 20 Piscium, which itself is located 4.8° south of lambda Pisces, the southeasternmost star of the Circlet asterism.

Uranus, in Aries, is just 9° east of Jupiter, and rises around 1:30amEDT at mid-month. To locate it, first find Botein (delta Arietis), a magnitude 4.4 star located about 9° southwest of the Pleiades, then move 2.4° southeast. The waning gibbous Moon lies 4° to its west on the 12th.

We haven’t looked at Asteroid 4 Vesta in a few months, since it has been behind the Sun, but it is visible once again in the morning sky, and can be found traversing east-southeastward through the Hyades Cluster in Taurus during much of July. It passes just 1.0° north of Aldebaran (alpha Tauri) on the 17th.

While still over 3 AU away, the brightest of the asteroids shines at magnitude 8.5, and can be tracked in binoculars. It will eventually brighten to magnitude 6.4 late this year.

On the 1st, the waxing gibbous Moon is 1.4° west-northwest of Antares (alpha Scorpii). The waning crescent Moon passes near Jupiter on the 11th and 12th.

The Full Buck Moon occurs at 7:38am on the 3rd. This will be the lowest Full Moon of the year, culminating just over 19° above the southern horizon at 12:33am on the 3rd.

After passing Last quarter Moon on the 9th, the 25.4-day waning crescent Moon passes 2.0° south of the Pleiades cluster on the 13th.

New Moon occurs on the 17th.

On the 23rd, the 5.7-day waxing crescent Moon is 2° south-southwest of the magnitude 2.7 binary star Porrima (gamma Virginis).

Ceres, at magnitude 8.5, is moving southeastward through Virgo. On the 8th, it passes 1.6° south of the elliptical galaxy M49.

The stars above have returned to their summer positions. In the west, we have finally bid farewell to the last remaining stars of winter, as Pollux and Castor, the twins of Gemini, have dipped below the western horizon. Ursa Major is now fully west of the meridian, and positioned nose-down, with the Big Dipper asterism pouring out its cosmic contents high above the northwestern horizon.

Leo and Virgo, the prominent constellations of spring, are low in the sky, and will have slipped out of view by midnight.

The Summer Triangle, consisting of the stars Deneb in Cygnus, Vega in Lyra, and Altair in Aquila, is high in the east. Hercules and Ophiuchus are now best viewed during mid-evening hours high in the south.

Now most prominent in the south in the evening sky, are our familiar summer constellations Scorpius and Sagittarius. Scorpius seldom gets the same attention as Sagittarius because of the latter being home to some of the MIlky Way’s brightest and largest nebulae and star clusters, but there are a few celestial delights worth noting around the scorpion.

Because of Scorpius’s low position in the sky, and that it is visible during the time of year that we typically have our most cloudy and hazy nights, we don’t get much time to explore this beautiful constellation, so it is worth planning to find a clear, moonless night, and a location with an open, southern horizon to visit Scorpius with binoculars or a small telescope.

Scorpius is one of the few constellations that resembles its namesake, with a set of claws extending towards its northwest, and a long, curving body ending in a hooked tail in the southeast. Antares, the brightest star in the constellation, marks the scorpion’s heart, and is truly massive. At over 15 times the mass of the Sun, Antares is a red supergiant star, nearing the end of its life. Antares shines with a luminosity of about 10,000 times that of the Sun, and lies about 550 light years away. If Antares were to take the place of the Sun in our solar system, all of the four inner planets, as well as much of the asteroid belt, would lie within its 3 AU radius.

Admiring Antares in a lo- power telescope, you may notice a patch of light 1.3° to its west. A bit of magnification will reveal a sparkling ball of stars that is the globular cluster M4. One of the closest globular clusters to us, at 6,000 light years distant, it is around eleven times the distance to Antares. Both objects are stunning to view simultaneously in a telescope.

At the far southeastern limit of the constellation, just near its “stinger,” is a pair of notable star clusters. If they were located farther north, they would likely get as much attention from observers as the Pleiades in Taurus or M44 in Cancer.

The northern of the two clusters, M6, was a clue on a recent episode of the TV game show Jeopardy! The clue read something to the effect, “Known as Messier 6, this star cluster in the constellation Scorpius represents this insect.” As often the case on Jeopardy!, the clue doesn’t presume that the contestants will be able to identify a Messier object by its number, but to name the associated insect, as in this case they did, correctly naming it the Butterfly Cluster.

The Butterfly Cluster contains over 100 stars, with many members being between 6th and 8th magnitude, extending over an area slightly smaller than the Full Moon. Its somewhat symmetric shape, with an axis of closely-spaced stars running roughly north-northwest to south-southeast lends it its name.

About 3.5° to the southwest is the second of the two clusters, M7, also known as Ptolemy’s Cluster, named after the 2nd century astronomer. This cluster contains far fewer stars than M6, about 25 or so, is slightly larger than M6, and having more brighter member stars than M6, makes it an ideal binocular object, a great starting point for your annual summertime journey into the Milky Way’s best sights.