The Sky in October

Meteor Showers

Draconids

Peaks October 8-9Orionids

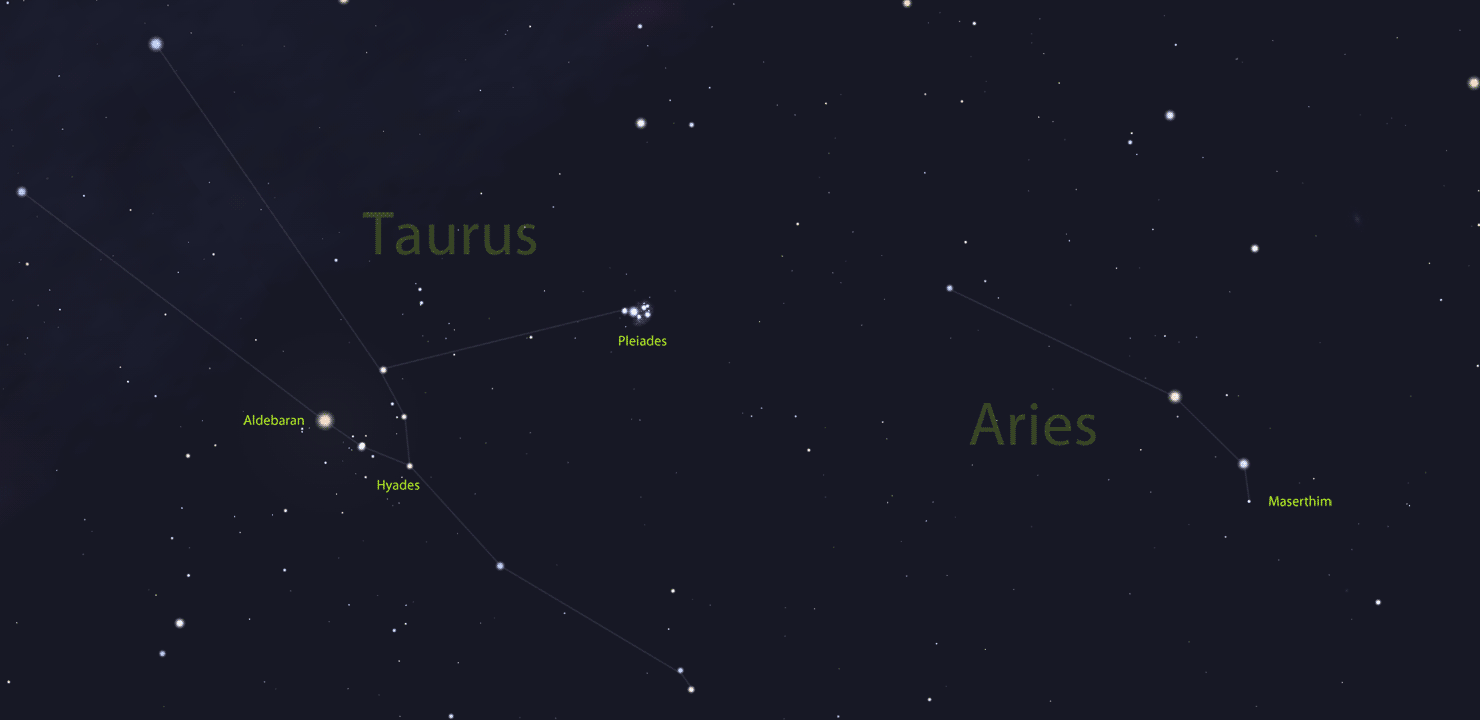

Peaks October 20-22October Constellations & Folklore

By Francine JacksonObserving Projects for October

Cygnus the Swan

: By Dave HuestisSome Bright Autumn Double Stars

: By Glenn ChapleM74: Galaxy in Pisces

: By Glenn ChapleA Selection of Double Stars in Cygnus

: By Glenn ChapleA Selection of Double Stars in Draco

: By Glenn ChapleA Selection of Double Stars in Andromeda

: By Glenn Chapleβ Cygni (Albireo)

: By Glenn ChapleA White Dwarf You can Actually See!

: By Craig CortisChaple’s Arc

: By Glenn ChapleEpsilon Pegasi: The Pendulum Star

: By Glenn ChapleCygnus X-1: A Black Hole You Can Find!

: By Craig CortisBeta Persei (Algol, the "Demon Star")

: By Glenn Chaple

NGC 7293: the Helix Nebula

: By Glenn Chaple

The “Little Big Dipper”

: By Jim HendricksonOmicron Ceti (Mira, the “Wonderful”)

: By Glenn ChapleThe Milky Way

: By Glenn Chaple

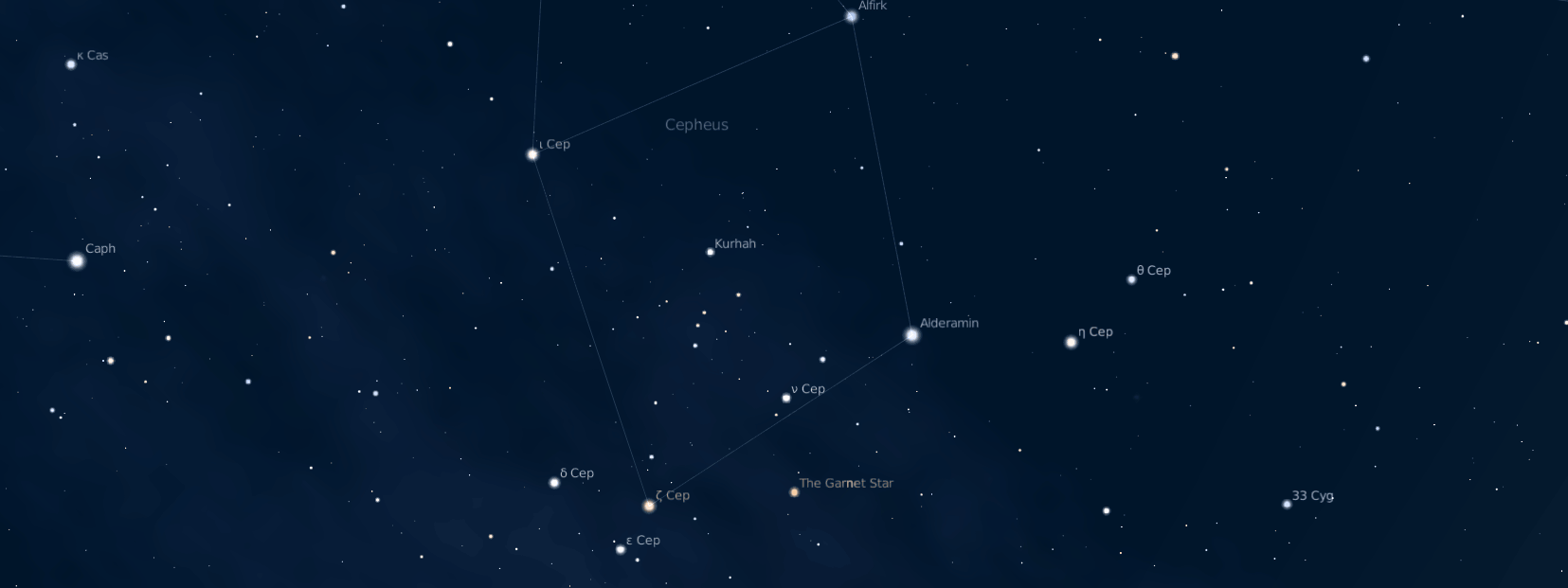

Delta (δ) and Mu (μ) Cephei

: By Glenn Chaple

NGC 457 (the “ET Cluster”)

: By Glenn Chaple

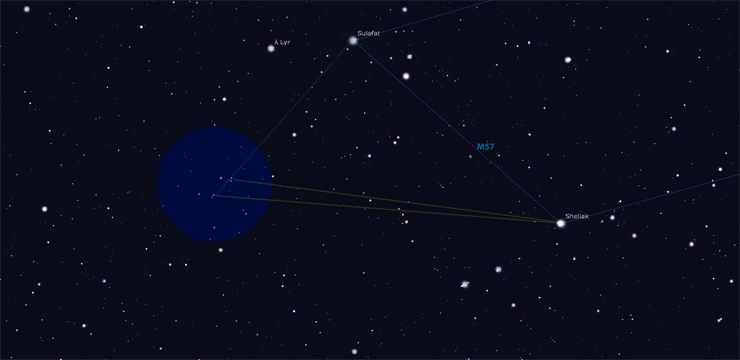

The Ships of Sheliak

: By Jim HendricksonM56: Globular Cluster in Lyra

: By Glenn ChapleOctober Constellations & Folklore

: By Francine JacksonObserve Delta Cephei

: By Gerry DyckAlmach

: By Glenn ChapleM33: Galaxy in Triangulum

: By Glenn ChapleNGC 6939: Open Cluster in Cepheus

: By Glenn Chaple

NGC 891: Edge-on Galaxy in Andromeda

: By Glenn Chaple

Kaffaljidhma: Double Star in Cetus

: By Glenn Chaple

Fomalhaut

: By Francine Jackson

M31: The Great Galaxy in Andromeda

: By Francine Jackson

Coathanger Asterism in Vulpecula

: By Glenn ChapleNGC 6934: Globular Cluster in Delphinus

: By Glenn ChapleStruve 2816 and 2819: Triple and Double Stars in Cepheus

: By Glenn Chaple