The Hyades: More than Meets the (Bull's) Eye

February 2021 :

Note: This article may contain outdated information

This article was published in the February 2021 issue of The Skyscraper and likely contains some information that was pertinent only for that month. It is being provided here for historical reference only.

Taurus is one of the most prominent constellations in the sky. Positioned high overhead during mid-winter evenings, the celestial bull is notable for three attractions, all visible to the unaided eyes. First, the constellation is roughly centered around the first magnitude K giant star Aldebaran. Part of the larger Winter Hexagon or Heavenly G asterism, Aldebaran is commonly associated with the eye of the bull, but its name is derived from Arabic and loosely translates to “follower,” because it rises immediately behind the Pleiades, the constellation’s most well-known star cluster. While the Pleiades needs no introduction, Taurus’ second large and bright cluster seems to attract far less attention, unless the Moon or Venus happens to be passing in front of it.

At a distance of about 150 light years, the Hyades is the second-closest known star cluster to our solar system, after the Ursa Major Moving Group. Many will be surprised to learn that Aldebaran is not associated with the cluster, despite its apparent position along its southeastern edge, Aldebaran is actually a foreground star, lying just 67 light years away, less than half the distance to the Hyades. The cluster is usually described as the 3-degree wide V-shaped asterism extending westward from Aldebaran, then angling back northward where the opposite open end of the V is just north of Aldebaran. It is a stunning sight in binoculars, and a small telescope will reveal about two dozen stars.

But, upon a closer look, it is clear that the Hyades is not as tightly confined and distinct as the Pleiades. This is due to the Pleiades being about three times as distant as the Hyades, and because the Pleiades is a much younger cluster, only about 100 million years, compared to the Hyades's estimated age of 625 million years. A leisurely perusal of the sky surrounding the Hyades with binoculars reveals many nearby stars similar to the Hyades, both in brightness and in scatter density, but apparently separated from the familiar V-shaped asterism forming much of the head of Taurus. An example is Davis’s Dog asterism, just a few degrees north of Aldebaran. There is also a scattering of stars southeast of Aldebaran. Are any of these stars near the Hyades, not just in angular separation, but in physical space? Is there more to the Hyades than initially meets the eye?

We can consult the data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission to determine this. By taking a survey of the parallaxes of these stars, we can determine their distance, and by analyzing their proper motions we can determine if they have a common trajectory through space. Together, these two pieces of information give us a good idea of what a star cluster looks like in three-dimensional space.

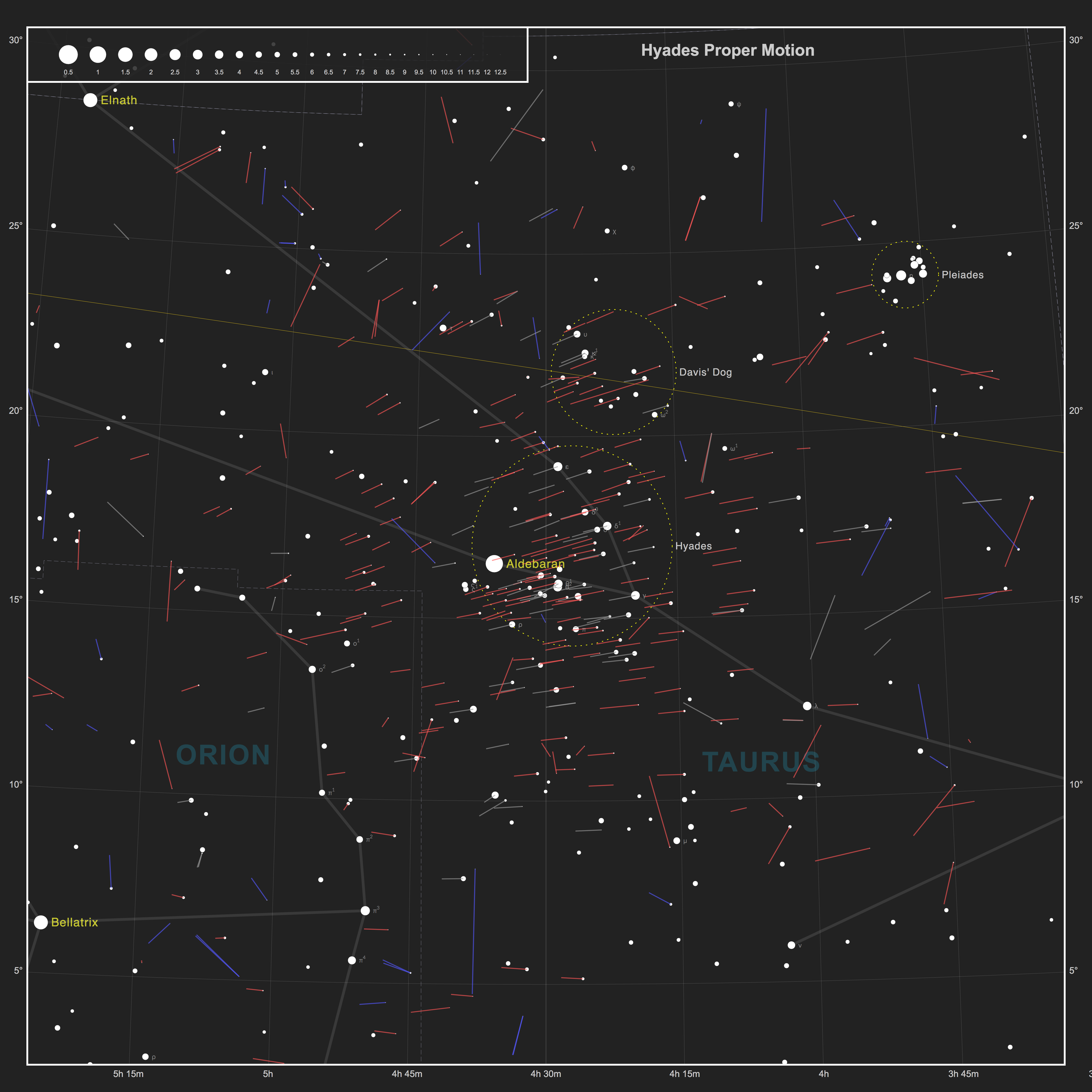

Using an equatorial chart plotted with the Yale Bright Star Catalog (BSC) as a base reference, let’s start by querying all of the stars within 15 degrees of the approximate center of the Hyades cluster (RA: 4h 28m, Dec: +17°). We can then compute a range of parallax to query the stars within 25 light years of the cluster’s approximate distance of 150 light years. This gives us a parallax range of 26.1 milliarcseconds (mas) to 18.6 mas.

Since proper motion data only gives us two-dimensional vectors, we can also query radial velocity data from Gaia to determine whether a star’s relative motion is towards or away from us, filling the three-dimensional picture.

The query results in just over 1,000 stars in this slice of sky.

Now that we have this data, we can plot them on our BSC reference chart using J2000.0 coordinates. Proper motions are plotted as line segments originating at the star’s astrometric coordinates, pointing in the direction of the angle computed from the RA and Dec components of the proper motion. Since milliarcseconds are too small to display at this scale, an arbitrary multiplier was chosen to make them distinguishable. Finally, the radial velocity is plotted by color. The red line segments indicate stars with a relative velocity moving away from us, and blue represents relative velocity towards us.

The resulting chart, which is limited to visual magnitude 12.5 for clarity, shows that a number of stars are related to the Hyades by means of their similar motion through space, including much of the Davis’s Dog asterism, several stars south of the main cluster, and many other stars scattered throughout southern Taurus and northwestern Orion. There are even some stars near the Pleiades, and near the shield of Orion. These stars are moving in a general east-southeast direction, as well as moving away from us at about 40 kilometers per second.

While many of these streams of stars may be outside of what we are traditionally familiar with as the Hyades cluster itself, visualizing their place in space relative to the stars around them gives us an interesting perspective of our neighborhood of the Milky Way. The next time you gaze up at this corner of the Winter Hexagon, don’t forget to explore beyond the familiar stars and asterisms, and remember that the sky is filled with so much beauty and knowledge that is waiting for us each time we look up.

Hyades photo by Bob Horton